Many a Zimbabwean has heard the words “change is change, let’s just take what we can get”. For women and the LGBTQ+ community, this sentiment is what has kept our issues and suffering on the back burner for decades. We are constantly told there are bigger questions to address and more essential bread-and-butter issues to fix before we can be afforded the basic dignities of freedom, safety and autonomy. Even though roughly 53% of voters are women, there is hardly any concerted effort dedicated to finally addressing our problems. That Zimbabweans are stuck between the oppression we know and the potential for something significantly worse is a perfect display of why progress in the African state is hard to come by. How exactly does one choose between a military state and a theocracy? Between police batons and the shackles of religious fanaticism? Within Zimbabwean political spheres, it is often impossible to tell whether we are moving forward or backwards.

Ever since I was a little girl, the risks of living in Zimbabwe have always been clear. Politics was a taboo word and a dangerous topic that induced fear. From the hushed rumours and whispers of assassinations and planned car crashes to harrowing stories of persecution and abuse like those of Jestina Mukoko, survival depended on how small you could make yourself. Silence was a given. You couldn’t dare to speak when your life was at stake and this has always been the reality of growing up in a military state.

I’ve fought my share of this fear. I’ve lived in the city long enough to have heard the pain of a grown man as he walked with a bullet hole in his foot. I have been a part of the crowd running home because I dared to go to work, dared to earn some money so I could live, but the police were in town that day. I’ve watched little girls cry from the glaring pain of teargas that was thrown in through the window in a house they thought was safe.

I earned my silence, earned my fear through years and years of bodies in black bags, teargas and burning houses. Silence is my safety. But as we approach the 2023 elections, I wonder if my silence will save me forever.

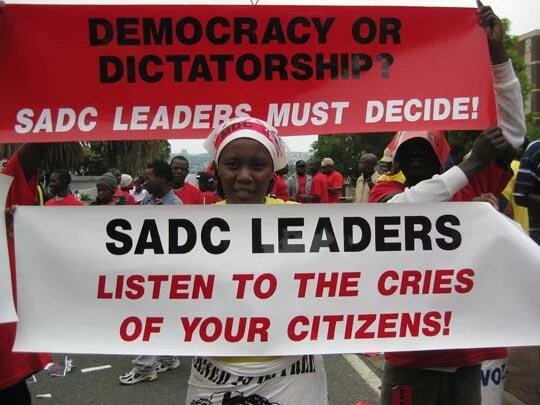

Historically, election time in Zimbabwe was a hard-fought battle, both figuratively and literally, between the ruling party, Zanu-PF, and the opposition, then the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). Only once, in 2008, did the opposition actually stand a chance to win the election, or so they thought. The fires of their victory were quickly stamped out by a series of political and military tactics that left them, once again, a disestablished opposition party with only as much freedom as was afforded them by Zanu-PF.

Again, the citizens suffered. Again, silence prevailed.

What change will come?

The upcoming Zimbabwean elections are shaping up to be a close race between Zanu-PF and the “new and improved” opposition, Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC), led by Nelson Chamisa. Both parties have made promises to improve the lives of Zimbabweans but there are some key differences between their platforms that could have a significant impact on the country’s youth, especially women and LGBTQ+ people.

The “change” in CCC’s name is important. Change is what the people of Zimbabwe have been yearning for. This is why the party has often been nicknamed “the people’s party”. A CCC victory would be a historic achievement for Zimbabweans as a whole and bring a change we have only had a brief glimpse of in the past 43 years.

My biggest fear is what exactly will this change look like.

We Zimbabweans are no strangers to change that is not true change. We had another near miss with our hope for change in 2018. This time, it was not a transition from one party to another but a coup within the ruling party that saw a transition of power from Robert G. Mugabe to Emmerson D. Mnangagwa. Zimbabweans celebrated this “change” with the enthusiasm of a people long oppressed and finally free; once again, this hope was quickly stifled. The militant tactics and systematic oppression that were a hallmark of Mugabe’s presidency have only intensified since. From soldiers firing live ammo into crowds of protestors to the passing of a law to ban criticism of the government as recently as June 2023, this change was a clear transition to a familiar but harsher form of oppression. The question is: is Zimbabwe once again in the same position?

Although I have lived through the many dualities of being a Zimbabwean citizen, I have lived these as a Queer, black woman. Like many Queer people living in this country, I have grown up with an added layer of fear. The first level of fear is induced by the hardships of self-acceptance but the second, more prominent, fear is the consistent threat of violence often induced by religious fanatics.

Zimbabwe has been far from a safe haven for women and the LGBTQ+ community. Small steps have been made toward progress. However, with homosexuality being an outright punishable offence and one in three women in Zimbabwe being the victim of sexual abuse, while one in four has suffered physical abuse, it has been made abundantly clear to us that Zimbabwe, as it stands, is not safe for us. Now, on the eve of this historic election, it may be the case that the potential “change” we are hoping for may also not include us.

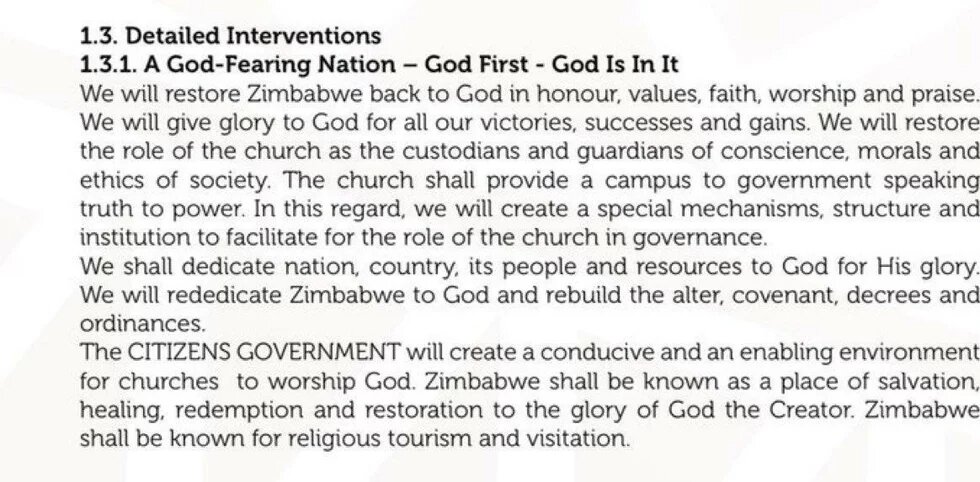

Through its 100-page manifesto, the CCC has made it clear that it wants to create a theocracy in Zimbabwe, with the government and the church working together to govern the country. This has raised concerns among Zimbabweans who fear that a theocracy would lead to the erosion of women’s rights and the persecution of LGBTQ+ people. There is a long history of such oppression. In Saudi Arabia, for example, women were only given the right to drive in 2018. In the UAE, women still require the permission of a male guardian to work or travel. LGBTQ+ people are also persecuted: 62 countries still criminalise homosexuality in their legal code, sometimes to the extent of the death penalty.

The CCC’s manifesto does not explicitly mention the rights of women or LGBTQ+ people with regards to the church, but it does say, “We will restore Zimbabwe to God in honour, values, faith, worship and praise” and promises to “rededicate Zimbabwe to God”.

This has led some Zimbabweans, including myself, to worry that the CCC could roll back the progress that has been made on LGBTQ+ and women’s rights in recent years. This fear is not unfounded. Just this year Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni signed an anti-LGBTQ law that includes the death penalty. Nelson Chamisa himself is on record multiple times expressing his religious-based stance against LGBTQ+ people. And women have seen our rights to our bodies come under attack by religious conservatives across the world. In the United States, the erosion of women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health and rights is accelerating as states and the Supreme Court move to severely restrict or ban access to legal abortion.

A report by the Jean-Jaurès Foundation and the feminist organisation Equipop found that women’s rights are regressing globally. This is the result of a coordinated effort by a diverse group of actors, including conservative parties and movements, religious fundamentalists and anti-rights groups. The Covid-19 pandemic further exacerbated inequalities, tripled women’s care burden and exponentially increased the violence, joblessness and precariousness they face.

Religion has no place in politics

This drive towards conservativism at the expense of basic human rights is what makes the possibility of a theocratic government so terrifying.

No matter how well intentioned a religion may be or seem, the integration of religion into politics tends to end in disaster and oppression. Shifting political and legal matters into the religious sphere creates a perfect environment for blind fanaticism to grow and turns any discourse regarding political change into an attack on religious values. This often leads to highly defensive and rigid measures that thwart any potential for change and ultimately stifle democracies and force dissenters into silence.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban recently moved to close down all salons in their drive to ban all women-only spaces because they are forbidden under sharia law. Sharia is a religious legal system that governs the spiritual, mental and physical aspects of a Muslim’s life. Based on the Quran and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, it is considered to be God’s law for Muslims. Therein lies the problem with a theocracy: there is no way to tell just how far one can go.

It is not clear how the CCC would implement its theocratic policies. According to its manifesto: “The church shall provide a campus to government speaking truth to power. In this regard, we will create a special mechanisms [sic], structure and institution to facilitate for [sic] the role of the church in governance.” However, it does not provide any details on how this would be achieved, how it would work and what limits the church would have in the country’s governance.

People have also criticised the CCC for its lack of political and economic strategy. The party’s manifesto is full of optimistic claims, such as promising that Zimbabwe will be a US$100 billion economy within a decade – although fewer than ten African countries currently have an economy of that magnitude. The growth pathway it provides also seems overly optimistic and out of touch with reality. Joseph Mandava, writing in the Herald, specifically questions the energy policy, citing how the changes reflected in the manifesto are not realistic considering Zimbabwe’s current economic state. Professor Jonathan Moyo criticised the CCC for plagiarising the 2018 MDC manifesto without editing and updating the statistics. In Moyo’s view, “It is a manifesto for the sake of it. A manifesto, especially from an opposition party, must have tangible, new deliverables, as opposed to claiming that we can do what the current government is doing better than them. The CCC needed a solid manifesto or programme of action if it wanted to be the next government.”

All of this has raised concerns about the CCC’s ability to govern Zimbabwe. The party needs to provide more details on how it would implement its policies and achieve its goals if it wants to win the trust of the Zimbabwean people.

Dignity is a bread-and-butter issue!

The Zanu-PF manifesto, on the other hand, while shrouded in its dark military history, does not centre theocracy or religion at all. Instead, it focuses on economic development and job creation. The party has not always been a friend to women and LGBTQ+ people and is known for backtracking on its promises, but Zimbabweans are starting to wonder, “Is the devil we know better than the one we don’t?”.

Many a Zimbabwean has heard the words “change is change, let’s just take what we can get”. For women and the LGBTQ+ community, this sentiment is what has kept our issues and suffering on the back burner for decades. We are constantly told there are bigger questions to address and more essential bread-and-butter issues to fix before we can be afforded the basic dignities of freedom, safety and autonomy. Even though roughly 53% of voters are women, there is hardly any concerted effort dedicated to finally addressing our problems.

That Zimbabweans are stuck between the oppression we know and the potential for something significantly worse is a perfect display of why progress in the African state is hard to come by. How exactly does one choose between a military state and a theocracy? Between police batons and the shackles of religious fanaticism? Within Zimbabwean political spheres, it is often impossible to tell whether we are moving forward or backwards.

As a Zimbabwean citizen, I too am ready for change, but I do not know whether the change my people seek is within reach. For most Zimbabweans in the upcoming elections, the decision lies in whether they want to risk a theocracy under the CCC or stay with the status quo under Zanu-PF. It is a difficult choice, but it is one that we must make for the sake of our future.

I suggest a third choice. Instead of the same two choices masquerading as change, we take a brand-new look at the other candidates. We listen to the voices of the people who are proposing real change, sustainable change. We build our nation from the inside out and ensure that our leaders have a plan for our future that does not include violence or discrimination.

I propose we change how we look at our choices, because not all change is good change – and no one is coming to save us.